“It’s a generational investment in the security of America and Americans,” Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth said.

Explaining the NNSA, latest agency hit by DOGE cuts

The NNSA within the Department of Energy is tasked with ensuring the nation’s nuclear arsenal is safe and secure, but it isn’t safe from DOGE cuts.

- Trump and Hegseth announced an initial funding request for the Golden Dome missile defense plan and tapped a Space Force general to lead the initiative.

- Missile defense experts argue that strategic defenses can help prevent wars, but arms control advocates have long held that they instead inspire deadlier nuclear weapons designed to defeat them.

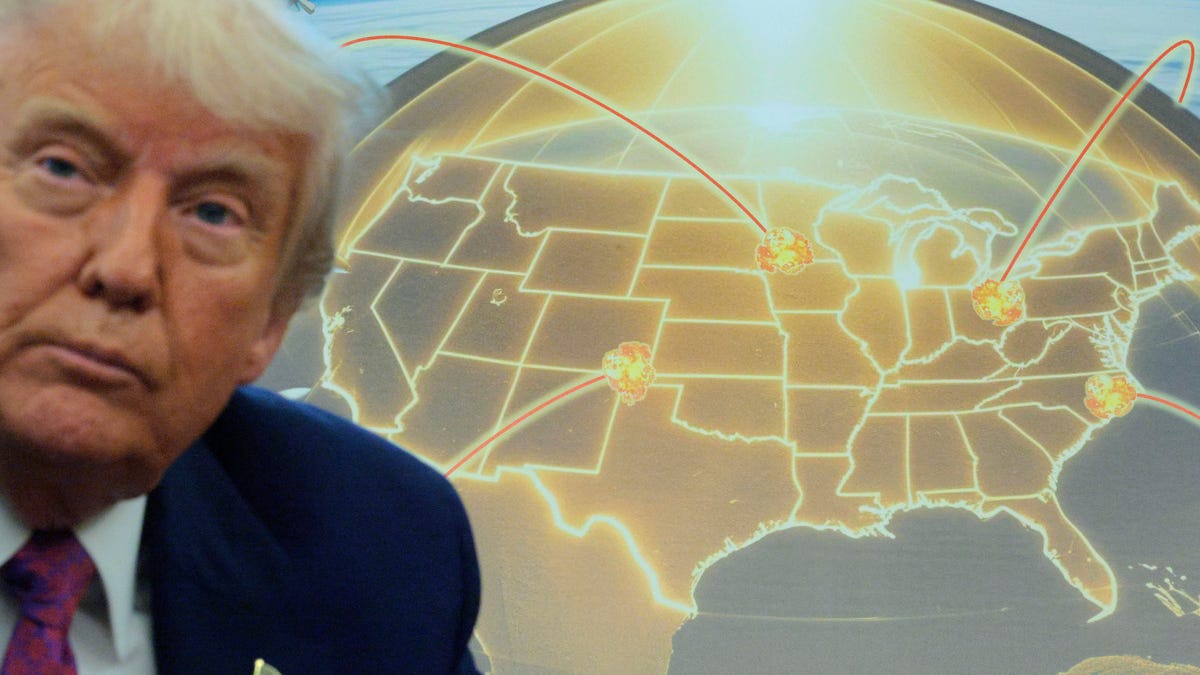

WASHINGTON − Cruise missiles. Ballistic missiles. Hypersonic missiles. Drones. All capable of nuclear strikes on U.S. soil.

President Donald Trump’s vision for a U.S. homeland safe from such threats moved forward when he and Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth announced a $25 billion initial investment in a “Golden Dome” shielding Americans. The president also said the system “should be fully operational before the end of my term,” in 2029.

“It’s a generational investment in the security of America and Americans,” said Hegseth.

The Golden Dome plan aims to cover the country with three layers of air defenses, according to written Senate testimony by Northern Command leader Air Force Gen. Gregory Guillot. Sensors will let the military see incoming threats, ground-based interceptor missiles and future systems will target incoming ballistic missiles, and additional systems will deal with lower-altitude threats like hypersonic missiles and enemy drones.

The funding is included as part of the Trump-endorsed tax cut megabill currently working its way through Congress, the president said.

Trump and Hegseth tapped Space Force Gen. Michael Guetlein to lead Golden Dome efforts, as POLITICO first reported. In remarks to reporters, Guetlein described the project as a “bold and aggressive” counter to worsening threats from adversaries like Russia and China.

Military officials, experts, and intelligence agencies warn the U.S. homeland is vulnerable to strategic attack. Many of the Golden Dome’s projected capabilities remain on the drawing board, though, and its cost will depend on its desired scale.

Trump said the system will cost $175 billion, though details about that estimate remain unclear, such as how much of it represents an increase to future-generation tech research as opposed to expanding existing technologies. It’s also unclear how effective a system relying solely on existing tech would be if it were to face down a mass nuclear attack from Russia or China.

A May 5 report from the non-partisan Congressional Budget Office estimated that deploying and operating a bare-bones space-based capability to intercept one or two incoming ballistic missiles would cost at least $161 billion over two decades. (CBO officials said in the report they are still calculating the estimated operating cost of the more expansive capabilities sought for the Golden Dome.)

The plan is not without its skeptics.

Sen. Angus King, I-Maine, pressed top military missile defense officials in a May 13 congressional hearing, asking top brass whether “we could deny a substantial missile attack from Russia or China.” In recent years, the military has invested roughly $8 billion in missile defenses for the island of Guam, a U.S. territory in the western Pacific that is home to nearly 170,000 people.

“If we’re talking about providing the level of defense that we have on Guam for our (mainland) citizens … we’re talking about an awful lot of money,” King said. He questioned whether the country should instead further invest in the nation’s beleaguered nuclear arsenal modernization push, which will cost nearly $1 trillion between now and 2034.

“I’m all for protecting the homeland, it’s just a question of how much will it cost relative to other defense needs,” the senator added. He argued that directed energy beam technology currently under development, if realized, presents the best long-term solution to the cost issue.

Arms control advocates have traditionally argued that increased missile defense makes the world less stable because it inspires adversaries to develop new offensive weapons that can defeat such defenses. During the Cold War, Soviet officials feared that U.S. missile defense efforts were meant to enable America to launch a surprise nuclear attack without fear of retaliation.

But some missile defense experts, including Tom Karako of the Center for Strategic and International Studies, claim that recent conflicts show the paradigm has changed around the use of non-nuclear missiles against strategic targets far behind the front lines.

Karako said the largely successful multinational defense of Israel from an April 2023 Iranian ballistic missile attack “prevented a war” and offers an illustrative example.

“If some large fraction of those 550+ projectiles got to Israel … there would have been a massive reprisal,” Karako said, arguing the episode is a “case study in how … fairly effective air and missile defenses contribute to strategic stability.”

Space is part of today’s battlefield, Karako said, and framing the issue of missile defense as one of strictly nuclear attack prevention is outdated.

“The 1980s called, and they want their arms control and disarmament discussions back,” he said. “We are facing a very different situation today.”

If you have news tips to share about the Golden Dome or other nuclear matters, please contact Davis Winkie via email at [email protected] or via the Signal encrypted messaging app at 770-539-3257. Davis Winkie’s role covering nuclear threats and national security at USA TODAY is supported by a partnership with Outrider Foundation and Journalism Funding Partners. Funders do not provide editorial input.