Historians and activists say its important to protect sites like the Harriet Tubman visitor center, which tell stories of many pasts.

Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Visitor Center upholds her legacy

The Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Visitor Center is one of two national historical parks keeping the abolitionist’s legacy alive.

CHURCH CREEK, MD ‒ Deanna Mitchell pointed to the bronze bust of Harriet Tubman at the center’s entrance and urged visitors to touch the nape of its neck to feel the scars.

The bust, she explained, faced North where Tubman had led dozens of enslaved people to freedom.

“It was a dark time,’’ said Mitchell, superintendent of the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Historical Park, which includes a visitor’s center.

Tubman has been the subject of renewed public interest in recent weeks, since the Trump administration briefly removed information about the abolitionist from the National Park Service’s website.

The Tubman picture and quote were restored after a public uproar, but the move raised alarms amidst other instances of Black and Native American figures being temporarily removed from federal websites.

In President Donald Trump’s first three months, he has repeatedly taken aim at what he’s criticized as unfair “woke” policies to promote DEI, or diversity, equity and inclusion. As part of that critique, he has targeted the “revisionist” telling of American history, which emphasizes events he describes as negative.

“Over the past decade, Americans have witnessed a concerted and widespread effort to rewrite our Nation’s history, replacing objective facts with a distorted narrative driven by ideology rather than truth,” Trump wrote in a March 27 executive order.

In recent years, the National Park Service has touted its efforts to preserve the histories of underrepresented groups, spending millions last year alone to restore and build sites that share the stories of abolitionists like Tubman, along with Japanese interned in World War II and nearly forgotten Mexican farmworkers.

But a number of historians, civil right activists and educators worry those kinds of efforts may be scaled back or even eliminated as the Trump administration reshapes how the government presents America’s past.

“Very few serious historians, scholars or cultural experts think the problem in America is that we have talked too much about our history of racial injustice, the history of slavery and lynching and segregation,” said Bryan Stevenson, founder of the Equal Justice Initiative, a human rights organization. “The problem has been the opposite.”

And Meeta Anand, senior director of Census and Data Equity at The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, sees the federal changes as an attempt to control the story of America.

“It represents a very deliberate effort to erase certain communities and the contributions communities have made,” she said.

‘History has tentacles’

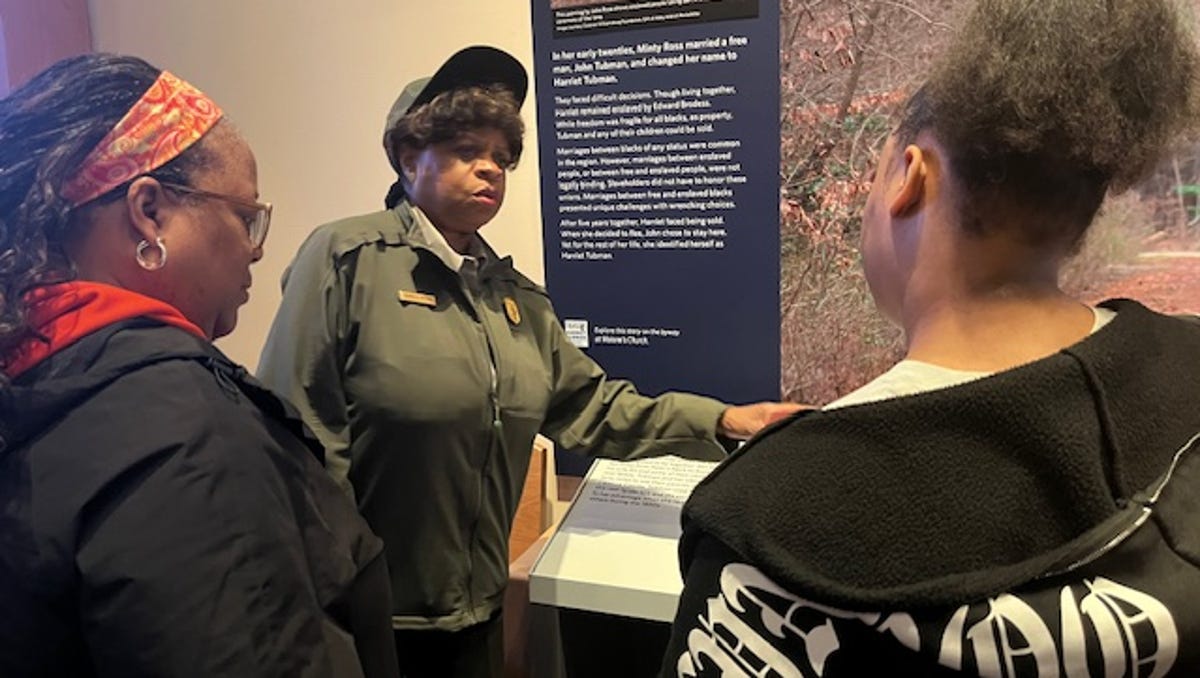

On a recent Wednesday, Mitchell led visitors through exhibits telling the story of Tubman’s life. She explained how the abolitionist braved death to help family and other enslaved Black people escape along the Underground Railroad.

“She lived a long life based on what she had to endure,” Mitchell told them.

The center is one of two National Park Service sites telling Tubman’s story. The other is in Auburn, New York, where Tubman later lived until her death at 91.

The center, co-managed by the Maryland Park Service, had 30,000 visitors last year. Many had been there before.

“Visitors actually are putting themselves in the space where she was and then they’re learning through guided tours,” Mitchell said. “They’re learning through tactile objects that they can touch and get information from.”

Mitchell said she hasn’t heard about any proposed cuts to the center and the staff is working hard as it always has to help people better understand history.

Just last April, the National Park Service touted $23.4 million in grants for 39 projects that aimed to preserve sites and stories about African American efforts to fight for equal rights.

Over the years, the National Park Service evolved from a focus mostly on nature and parks to include sites with rich histories, Mitchell said.

“We realized as a service that history has tentacles,’’ she said. “And there are cultural aspects of our history that need to be preserved and protected.”

‘You want people to know the history’

The Reidy family studied a map outside the Underground Railroad Visitor Center looking for other Tubman sites to explore.

Tim and Kim Reidy brought their children, Elizabeth, and Sam, to the center to learn more about Tubman. They were on a spring break trip from Westchester, New York.

“It seemed like an important and historically relevant aspect of the history of the place to bring them to,’’ said Kim Reidy. “I’m glad that places like this exist.”

Elizabeth, 15, had learned about Tubman in school, but she said “it’s so important to have museums and these spaces dedicated to this.”

Tim Reidy said the family may also visit the Tubman center in Auburn.

“It’s one thing to read about it, but to be in the actual physical space is a whole different experience,” he said. “You can see why people want to come here. You don’t want to lose that.”

Rhonda Miller of Bowie, Maryland, and her daughter, Madison, followed along as Mitchell, the superintendent, led them on a tour of the Tubman center.

Miller and other members of Parents Helping Parents Together, a support group for parents of children with special needs, had traveled two hours to the center.

Miller grew up learning the basics about Tubman and she and Madison had watched the 2019 movie, “Harriet.”

“This was building on that, actually going to see places where she may have walked,” Miller said. “I love the way they put this museum together and presented the information. It was really amazing.”

Miller said with efforts to erase Black history it was particularly important that Madison also learn about it outside the classroom.

“I would hate to see places like this disappear,” Miller said after the visit. “We need them.”

‘Treat our history with the respect’

A few miles from the center in downtown Cambridge, William Jarmon gathered visitors at the Harriet Tubman Museum and Educational Center to share her history. Tubman spent the first 27 years of her life enslaved in the region.

The small museum featured portraits of Tubman and exhibits. A mural of Tubman with an outstretched hand was painted on the side of the building.

There are also other nods to Tubman’s legacy in the county, including a statue outside the courthouse.

Jarmon, president of the Harriet Tubman Organization, a nonprofit that runs the museum, said it relies in part on tours it offers and local support to continue its mission.

“We are making it our business to reach every generation, especially through the schools so that they will understand that it’s just not her story, but it’s all of our stories,” Jarmon said.

Stevenson said institutions that receive federal funding are feeling pressure to roll back diversity programs.

The Equal Justice Initiative has three sites in Montgomery, Alabama, focused on the Black experience, including a new sculpture park. The programs are privately funded.

“I hope this is a short-term problem because I really believe that the majority of people in Congress don’t want to defund our major museums and institutions, even if they don’t agree with every sentence in those museums,” Stevens said.

Some groups, including faith leaders, have stepped up to teach more Black history .

Others have increased their support of Black-run museums and programs, said Cliff Albright, co-founder of Black Voters Matter. Still, he said, taxpayer-funded institutions should include that history.

“Our expectation is that they treat our history with the respect that it deserves, even as some of us are looking at ways that we can ensure that that history gets maintained,” Albright said.

Those efforts shouldn’t let up, Stevenson said.

“What we should not do is retreat from truth telling, retreat from honest and accurate history, from providing the full story,’’ he said. “That’s a recipe for disaster, for fostering ignorance.”