The consequences of DOGE’s disruptions at the National Nuclear Security Administration could be far-reaching, expert say.

Explaining the NNSA, latest agency hit by DOGE cuts

The NNSA within the Department of Energy is tasked with ensuring the nation’s nuclear arsenal is safe and secure, but it isn’t safe from DOGE cuts.

- For decades, the NNSA has struggled with federal staffing shortages that have contributed to safety issues as well as delays and cost overruns on major projects.

- Experts fear that the Trump administration’s moves to reduce the federal workforce may have destabilized the highly specialized federal workforce at the National Nuclear Security Administration.

- USA TODAY reviewed decades of government watchdog reports, safety documents, and congressional testimony on U.S. nuclear weapons.

In 2021, after a pair of plutonium-handling gloves had broken for the third time at the Los Alamos National Laboratory, contaminating three workers, and after the second accidental flood, investigators from the National Nuclear Security Administration found a common thread in a plague of safety incidents: the contractor running the New Mexico lab lacked “sufficient staff.”

So did the NNSA.

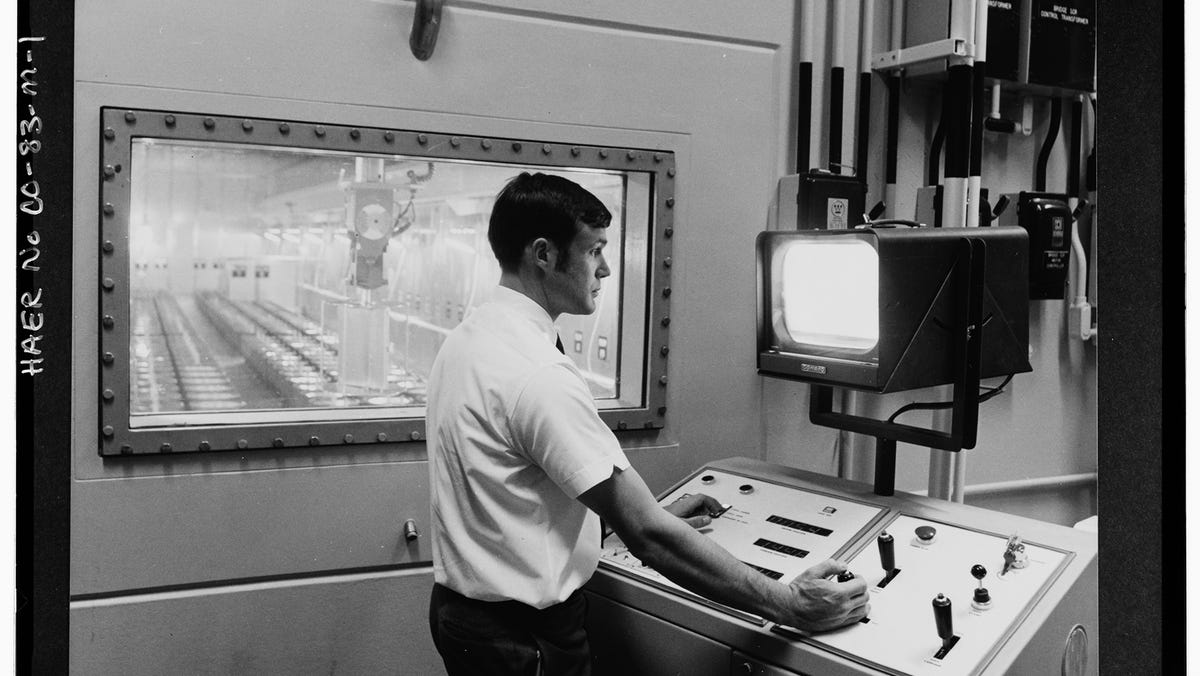

The agency, whose fewer than 1,900 federal employees oversee the more than 60,000 contractors who build and maintain the U.S. nuclear arsenal, has struggled to fill crucial safety roles. Only 21% of the agency’s facility representative positions – the government’s eyes and ears in contractor-run buildings – at Los Alamos were filled with qualified personnel as of May 2022.

Now, President Donald Trump’s administration has thrown the NNSA into chaos, threatening hard-won staffing progress amid a trillion-dollar nuclear weapons upgrade. Desperately needed nuclear experts are wary of joining thanks to chaotic job cuts by Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency, experts say.

The disruption of NNSA’s chronically understaffed safety workforce is “a recipe for disaster,” said Joyce Connery, former head of the Defense Nuclear Facilities Safety Board.

Los Alamos is not the only facility with staffing shortages in crucial safety roles.

As of May 2022, less than one-third of facility representative roles at NNSA’s Y-12 facility in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, and the Pantex plant near Amarillo, Texas were held by fully qualified employees, according to a USA TODAY review of nuclear safety records.

At Pantex, where technicians assemble and disassemble nuclear weapons, only a quarter of safety system oversight positions had fully qualified hires, and only 57% of those safety positions had qualified employees at Y-12.

Nuclear weapons workers don’t grow on trees, nor do the federal experts who oversee them. Many of the jobs require advanced degrees, and new hires often need years of on-the-job training. Security clearance requirements limit the most sensitive jobs to U.S. citizens.

America’s nuclear talent crisis isn’t new, but its consequences have grown as tens of billions of dollars pour into the NNSA annually in a broader $1.7 trillion plan to modernize U.S. nuclear weapons.

Congress ordered the cramped, aging plutonium facility at Los Alamos – called PF-4 – to begin mass production of plutonium pits, a critical component at the heart of nuclear warheads, for the first time in more than a decade.

Enter Elon Musk and DOGE.

After nearly three decades of bipartisan effort, lawmakers and NNSA officials believed they had turned a corner in a long-running “war for talent.” Reaching 2,000 NNSA employees was a major accomplishment after a record hiring year in 2024, but there was a long way to go: an internal staffing study found the agency still needed around 700 additional employees.

Then came Trump and Musk’s “fork in the road” resignation program, followed by the chaotic firing of over 300 NNSA federal employees in February.

Although the agency ultimately reinstated all but a handful of the fired workers, the move crushed morale and left current and prospective talent uncertain about stability − one of federal employment’s greatest benefits when compared with lucrative private sector jobs.

To understand what’s at stake amid the NNSA’s workforce woes, USA TODAY interviewed current and former agency officials and reviewed decades of watchdog reports, safety records and other official documents.

Destabilizing the NNSA’s federal workforce risks delaying and further driving up the cost of the nuclear arsenal modernization effort, according to documents and experts.

Marvin Adams led the NNSA’s defense programs as deputy administrator from April 2022 until January 2025.

“I worry that understaffing will cause delays, ultimately, in our delivery of warheads to the military,” Adams told USA TODAY. Other experts say DOGE’s rupture of the talent pipeline could also impact the safety of workers – and local communities – by harming safety oversight.

An NNSA spokesperson said the agency “has determined recent staffing reductions remain manageable.” The spokesperson confirmed NNSA is under a hiring freeze save for “some … positions that are mission critical.”

The Government Accountability Office, since 1990, has said the NNSA and its predecessor agencies were at “high risk” of fraud, waste and abuse in oversight of government contracts. Many of the agency’s cost overruns are attributable to staffing problems, according to watchdogs.

‘Mistakes’ and misgivings

Over the span of a few days in mid-February, a series of layoffs – many later reversed – rocked the NNSA. The agency had already been shaken by the loss of more than 130 employees to a DOGE deferred resignation program, according to the New York Times.

The voluntary departures weren’t unprecedented. When the NNSA implemented a buyout program to shrink its staff in the early 2000s, government watchdogs warned of skill gaps.

This time, though, key officials who left the NNSA voluntarily included hard-to-replace specialists like the uranium enrichment program director and a senior official tasked with scaling up production of plutonium pits.

The sudden departures left key offices shorthanded, disrupting highly choreographed succession plans that enable the NNSA to maintain continuity in roles that require months or years of on-the-job training.

Many of those who accepted DOGE’s deferred resignation offer rated among the agency’s best and brightest – those with the greatest chance of landing new roles in the private sector, said an NNSA employee. The employee requested anonymity due to fear of retaliation.

Musk’s team moved on to identifying probationary workers that agencies could quickly fire. These employees, many of whom were new hires or had recently received promotions, lacked full civil service protections.

According to Adams, most of the probationary employees at NNSA joined in 2024, a “record high” hiring year when understaffed warhead program offices finally made significant personnel gains.

The axe fell for more than 300 at NNSA overnight Feb. 13. One of those briefly fired, according to The Bulwark, was the agency’s acting chief of defense nuclear safety.

Los Alamos, where the recent spate of safety lapses occurred, sustained brutal cuts before the reversals. Its NNSA site office, which oversees the work of more than 14,000 contractors, lost its emergency preparedness manager, its radiation protection manager, its fire protection engineer, and two facility representatives, media reports said.

Lawmakers frantically asked Energy Secretary Chris Wright to reconsider. Wright first paused the cuts and then reinstated most of the fired employees.

Wright later issued a mea culpa: “I probably moved a little too quickly there, and when we made mistakes on layoffs in NNSA, we reversed them immediately, [in] less than 24 hours,” he told Scripps News.

But some damage can’t be repaired. And the bloodletting may not be finished either.

A recent Department of Energy review identified approximately 500 NNSA employees, or roughly one-fourth of the organization’s headcount, as non-essential, according to media reports. An agency spokesperson, though, said “there are no plans to execute a Reduction in Force … and NNSA employees were not eligible for the second round of the Deferred Resignation Program.”

Agency employees – and members of Congress – detailed a spiraling workplace climate at NNSA.

Two employees described an atmosphere of anxiety, suspicion, and rumors of surveillance. When asked about surveillance rumors, the agency spokesperson said employees “do not have a right nor should they have an expectation of privacy” while using government devices.

One employee described decrepit office spaces overflowing with people after the Trump administration ended remote work and ordered all federal workers back to the office.

The top Democrat on the Senate Armed Services Committee, Sen. Jack Reed, D-R.I., cited “morale … spiraling downwards because of these personnel changes and simply the lack of personnel” when questioning Brandon Williams, the Trump administration’s nominee for NNSA administrator, at an April hearing.

Sen. Angus King, I-Maine, told USA TODAY he is “concerned, generally, about being sure that we have adequate workforce and adequate expertise” in the NNSA’s federal workforce to ensure programs stay on-time and on-budget.

How to build bomb builders

As the 1990s ended, the U.S. nuclear weapons industry was in the throes of a talent crisis that emerged from the end of the arms race with the Soviet Union.

Congress established a commission to study how to salvage the nuclear talent pipeline as decreased production, plant closures, staffing cuts and an aging workforce threatened the country’s ability to maintain its nuclear stockpile.

Known as the Chiles Commission, after its chairman, retired four-star admiral Harry G. Chiles Jr., the group’s 1999 findings ring true for the NNSA today: a workforce uncertain about its future and job security, intense competition for technical talent – and a steady increase in the proportion of U.S. STEM degrees awarded to foreign students ineligible for classified weapons work.

Compounding those issues was the steady drain of expertise from an aging nuclear workforce. One early 2000s warhead program saw a $69 million overrun and delays because the NNSA forgot how to produce a classified material needed in the weapon, according to a 2009 GAO report.

In response to its struggles, the NNSA expanded its graduate fellowships, which began in the mid-1990s and grew into one of its top sources of early career employees.

Nearly two-thirds of fellowship alumni joined the nuclear workforce.

But that and other efforts have merely taken the edge off a persistent talent shortage – and a DOGE-directed hiring freeze has prevented the NNSA from hiring this year’s graduating fellows.

A 2024 GAO report highlighted additional struggles to acquire talent.

NNSA officials told the watchdog that other employers – including the very contractors who they oversee at U.S. national laboratories – often pay more, offer superior benefits, or permit remote work. Once the agency makes a hire, on-the-job training in the design and production of nuclear weapons can take “two or more years,” according to a 2023 management plan.

‘Weaponeers’ hard to come by

To earn an Energy Department Q security clearance, most workers must be U.S. citizens and regularly pass a battery of tests, interviews and evaluations to monitor physical and mental fitness.

Becoming a fully qualified “weaponeer,” as nuclear weapons engineers are known, can take up to a decade, even for a “scientist or engineer with an advanced degree,” Los Alamos officials told watchdogs.

“You can’t go to university and get a degree in how to make nuclear weapons,” Los Alamos National Laboratory’s director, Thom Mason, told the Defense Nuclear Facilities Safety Board in 2022.

What’s at stake

The struggle for staff has been NNSA’s Achilles heel for decades – and the stakes have only grown.

During his first term, former President Barack Obama struck a deal with Congress: if Senate Republicans backed the New START arms control treaty with Russia, Obama would support investing billions of dollars to modernize the country’s nuclear weapons.

But almost immediately, the NNSA struggled with that modernization.

In 2008, just before the upgrade program creaked to life, the Department of Energy told the GAO it “lacked an adequate number of federal contracting and project personnel with the appropriate skills” for major projects.

As workforce woes continued, projects blew their budgets and timelines.

The estimated price of a long-awaited new uranium facility at the Y-12 National Security Complex in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, increased by more than $5 billion in 2012 due to flawed cost estimates and oversight mistakes attributed in part to federal staffing shortages. The price tag has since increased to around $10.3 billion.

An effort to extend the life of the B61 nuclear bomb also faced significant delays and saw costs more than double – to the tune of an additional $4 billion. An agency official told auditors the NNSA needed “two to three times more personnel … to ensure sufficient federal management and oversight,” according to a 2016 report.

The NNSA battled to meet statutory targets in plutonium and lithium programs in the late 2010s due to staffing shortages. Adams, the former deputy administrator, witnessed similar strain more recently.

“I watched as our federal [warhead] program offices struggled to keep up and not get behind because of understaffing,” he said. “You don’t want to introduce delays because you don’t have enough federal people making or approving decisions in a timely manner.”

But despite efforts to develop talent, watchdogs said in February of this year the NNSA was “understaffed” and struggling to execute key oversight requirements.

Then came DOGE.

Adams said he is “concerned” the cuts and climate could have a “chilling effect on anyone considering joining the workforce” at NNSA. He argued the stakes are too high amid “China’s nuclear buildup and Russia’s saber rattling.”

Connery, the former safety board head, warned Americans could be at risk.

Technical safety oversight roles often require highly skilled professionals who have other employment prospects, and a sense of mission and stability plays a major role in drawing and keeping such talent, Connery argued. She also expressed concern over the Trump administration leaving vacancies on independent safety boards.

The safety situation only stands to grow more worrisome at Los Alamos, argued Dylan Spaulding, a nuclear security expert at the Union of Concerned Scientists.

Los Alamos is on overdrive due to the demand for plutonium pits. Congress mandated the NNSA produce 80 pits per year – 30 at Los Alamos, and 50 at a facility currently under construction in South Carolina – by 2030.

PF-4, the plutonium facility at Los Alamos, is aging and was never designed for mass production of pits. The facility was used primarily for research and development throughout the Cold War.

While the contractor at Los Alamos has successfully staffed up, progress at the NNSA site office has been more gradual.

“They really struggled over the past decade to overcome [staffing] problems so they could ramp up pit production,” Spaulding said. He described those gains as “at risk of eroding” and “fragile at best.”

Connery fears the strain and staffing problems could combine to disastrous effect.

“When you take an inexperienced or an understaffed workforce and you combine it with old facilities and a push to get things done – that is a recipe for disaster,” Connery said.

If you’re a current or former NNSA employee willing to inform USA TODAY’s coverage of the agency, please contact Davis Winkie via email at [email protected] or via the Signal encrypted messaging app at 770-539-3257. Davis Winkie’s role covering nuclear threats and national security at USA TODAY is supported by a partnership with Outrider Foundation and Journalism Funding Partners. Funders do not provide editorial input.